MAP PROJECT OFFICE AND MODEM WORKS

TEXT BY CLARE DOWDY

Nearly half of the world’s population lacks access to essential health services. Map Project Office partnered with Modem to develop a vision for universal healthcare, driven by generative AI technology. Smart Aid Kit presents a series of innovative medical devices, enabling individuals and communities to conduct basic triage without barriers.

When faced with a health concern, many of us can simply pick up the phone to call the doctor or head to a nearby hospital. While this is a reality for a sizable portion of the global population, digging deeper into the statistics reveals that for a large number of people worldwide, such access is more of a fantasy than a reality.

And yet, this is what our global institutions are striving for. They call it ‘universal healthcare coverage’, which the World Health Organisation defines as “all people having access to the full range of quality health services they need, when and where they need them, without financial hardship”.

The nations of the world established universal healthcare coverage as a target in 2015, when they adopted the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal. However, despite these good intentions, we’re not making sufficient progress.

And this is in spite of the great strides in medical science—just think of the lightning speed at which Covid vaccines were developed. Yes, advances in earlier or more accurate diagnoses, better treatments, and even cures make headlines practically every week. Yet, a vast number of people around the world still struggle to access healthcare.

Accessibility issues manifest in two key ways: the cost of care and the ability to see a clinician. In fact, one or both of these issues affect individuals differently depending on their location around the world.

In many places, patients face steep costs for treatment. In the United States, the PwC Health Research Institute forecasts a 7.0% increase in medical costs in 2024. Consider a retiree in the poverty-stricken Appalachian Mountains. Without personal transportation and health insurance, he may encounter difficulties in spotting early symptoms of diabetes.

In developing countries, the situation is even worse. According to the World Bank Group, people spend an astounding half a trillion dollars out of their own pockets on health services each year. This amounts to over $80 per person and disproportionately impacts the poor. Take, for instance, a woman and her daughter in Sierra Leone. Access to healthcare for them is a significant challenge. The nearest district hospital may be a considerable distance away, and financial constraints, such as surviving on a daily income of roughly $2, severely limit their options for transportation. Physical frailty due to illness further complicates their ability to seek medical attention. Under these conditions, the risk of their health deterioration escalates, underscoring the broader issue of healthcare accessibility.

Similarly, workforce shortages affect both affluent and impoverished nations alike. According to PwC, the challenges facing the U.S. are “compounded by clinical workforce shortages”. Even countries with some form of a national health service grapple with issues of accessibility, in part caused by a lack of healthcare professionals. As the Kings Fund puts it: “The UK’s health and care system is under intense pressure, with rising waiting times, persistent workforce shortages and patients struggling to access the care they need.”

High-income OECD countries, like the U.S., Canada and the UK, have around 3,000 doctors per million people, according to World Atlas. Any workforce shortages in wealthy nations seem insignificant when compared to the availability of medical professionals in the world’s poorest countries. There are 25 countries with 100 or fewer physicians per million people—not nearly enough doctors to go round. For example, a family in Liberia faces an uphill battle to find a doctor, as there are only ten for every million people—the lowest availability on record.

Healthcare is increasingly becoming a privilege that only benefits the wealthy, who can afford it, and the fortunate, who live near well-staffed, affordable facilities. For the vast majority of the global population, the harsh reality often means suffering from untreated pain or dying of a curable condition.

AI HEALTHCARE: PROMISES AND RISKS

Over the last decade, advances in technology have revolutionised American healthcare. According to the American Medical Association (AMA), doctors are rapidly embracing digital tools like telehealth and wearable devices for remote patient monitoring. As of 2022, an impressive 93% of U.S. physicians say these digital advancements are making a positive impact on patient care.

And now, recent advances in AI could soon make a big difference. Sophisticated Large Language Models (LLMs) are becoming increasingly prevalent and some are already being trained to provide high quality answers to medical questions. For example, Google's Med-PaLM is a game-changer in the field, capable of digesting and summarising complex medical literature. Not only does it set new benchmarks in medical competency, but it also made history by being the first LLM to score 'expert' levels on questions styled after the U.S. Medical Licensing Exam. Beyond text-based input from the patient, these state-of-the-art multimodal models can handle a wide spectrum of medical data—be it clinical jargon, medical images or genomics.

At the same time, it looks like advanced LLMs will soon function on virtually any device. One example of that comes from technology firm Qualcomm, which plans to integrate Meta’s Llama 2-based AI technologies into premium smartphones from 2024. This widespread availability of powerful AI on consumer devices could lay the groundwork for transformative applications in various sectors, including healthcare.

The consensus is that one day soon, people in disadvantaged areas globally will gain access to universal healthcare via generative AI. According to the Wall Street Journal, an internal email at Google suggests that its Med-PaLM model could be particularly helpful in countries where access to medical professionals is limited.

Or, as Bill Gates puts it: “Many people in developing countries never get to see a doctor, and AIs will help the health workers they do see be more productive. AIs will even give patients the ability to do basic triage, get advice about how to deal with health problems, and decide whether they need to seek treatment.”

However, it’s not as simple as applying a successful system from one location to another. A critical challenge that could affect technology’s efficacy is bias in an AI-based healthcare model. Most LLMs are developed in Western nations, utilising existing digitised health records for data. With this data, a western-centric perspective often dominates the field of AI in healthcare. This perspective can inadvertently lead to the development of solutions that are not universally applicable or accessible, thus perpetuating healthcare inequalities.To be as accurate in different parts of the world as they are in the West, AI tools will require millions of historical health data-points. These are needed to train their algorithms to give accurate advice relevant to the local geography and population. Unfortunately, this type of comprehensive health data is generally absent in low and middle-income countries.

A VISION FOR UNIVERSAL HEALTHCARE

Research by Modem Works and Map Project Office suggests the solution may lie in merging this ever-improving software with purpose-built hardware. They envision medical aids that are robust, easy to use, and embedded with sophisticated medical LLMs. Such a combination could be life-changing for those who are economically or geographically marginalised.

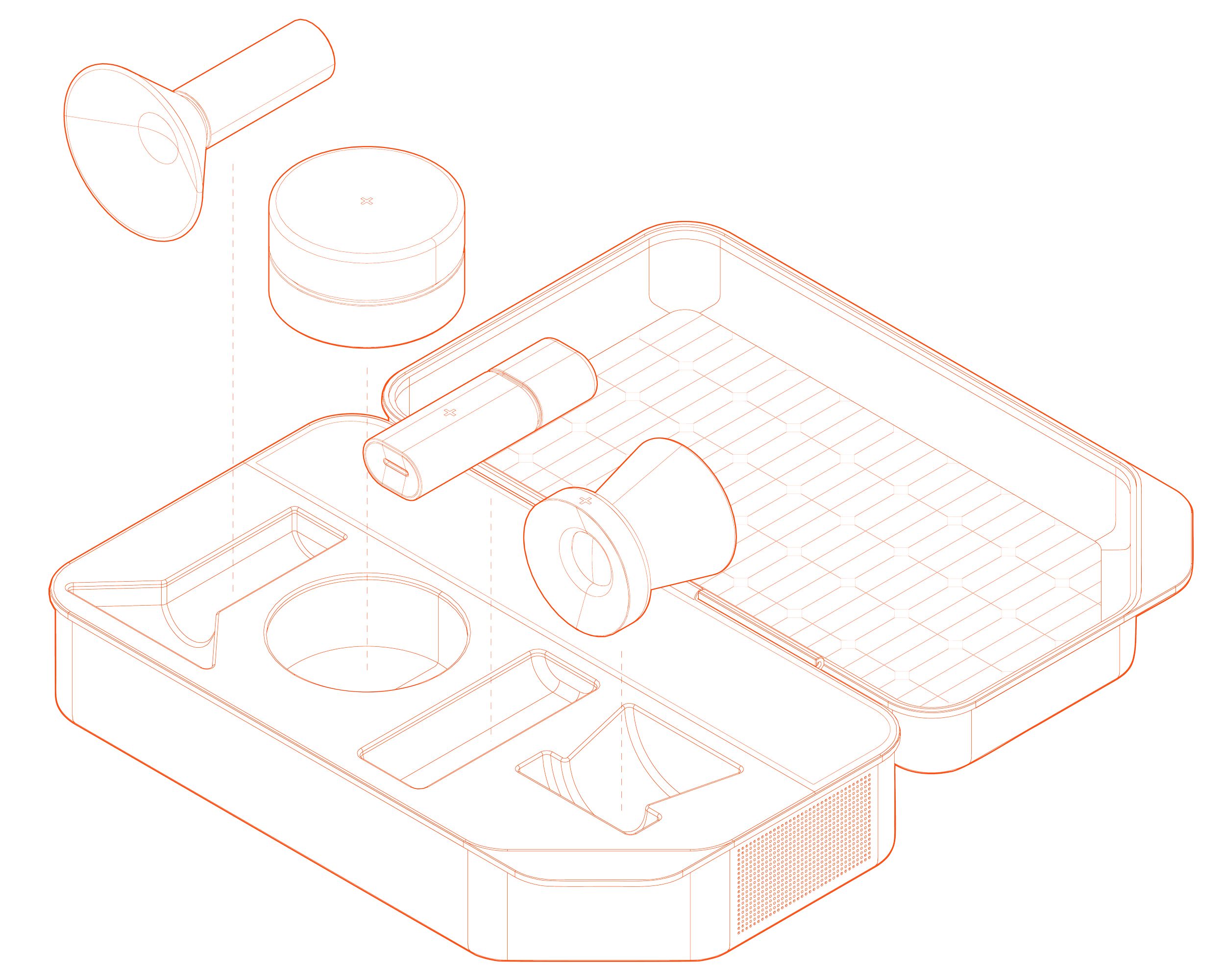

Smart Aid Kit features a durable case, equipped with its own mini-solar panels, and includes four essential medical devices powered by an advanced medical LLM. Designed for easy community access, the energy-efficient kit would be situated in public spaces, much like an Automated External Defibrillator (AED). The user interface guides individuals through a series of questions to determine which device they might need, similar to a consultation with a General Practitioner.

Within the kit, hand-held sensor devices scan and evaluate various health conditions. This data is transmitted back to the core unit housing the LLM, which can then diagnose conditions and offer immediate guidance on whether to seek further medical treatment.

Smart Aid Kit comes equipped with four essential devices: a stethoscope, spirometer, ophthalmoscope and a skin analyser. Each device is an innovative take on its traditional counterpart.

STETHOSCOPE

A stethoscope allows medics to listen to our bodies’ internal sounds. Smart Aid Kit’s stethoscope is an evolution of that. Its big white dome (or diaphragm) sits on the skin over the lungs, heart or bowels. Body sounds make the diaphragm vibrate, producing sound waves. These waves are relayed to the kit, where sensors measure and analyse temperature, blood pressure and oxygen saturation.

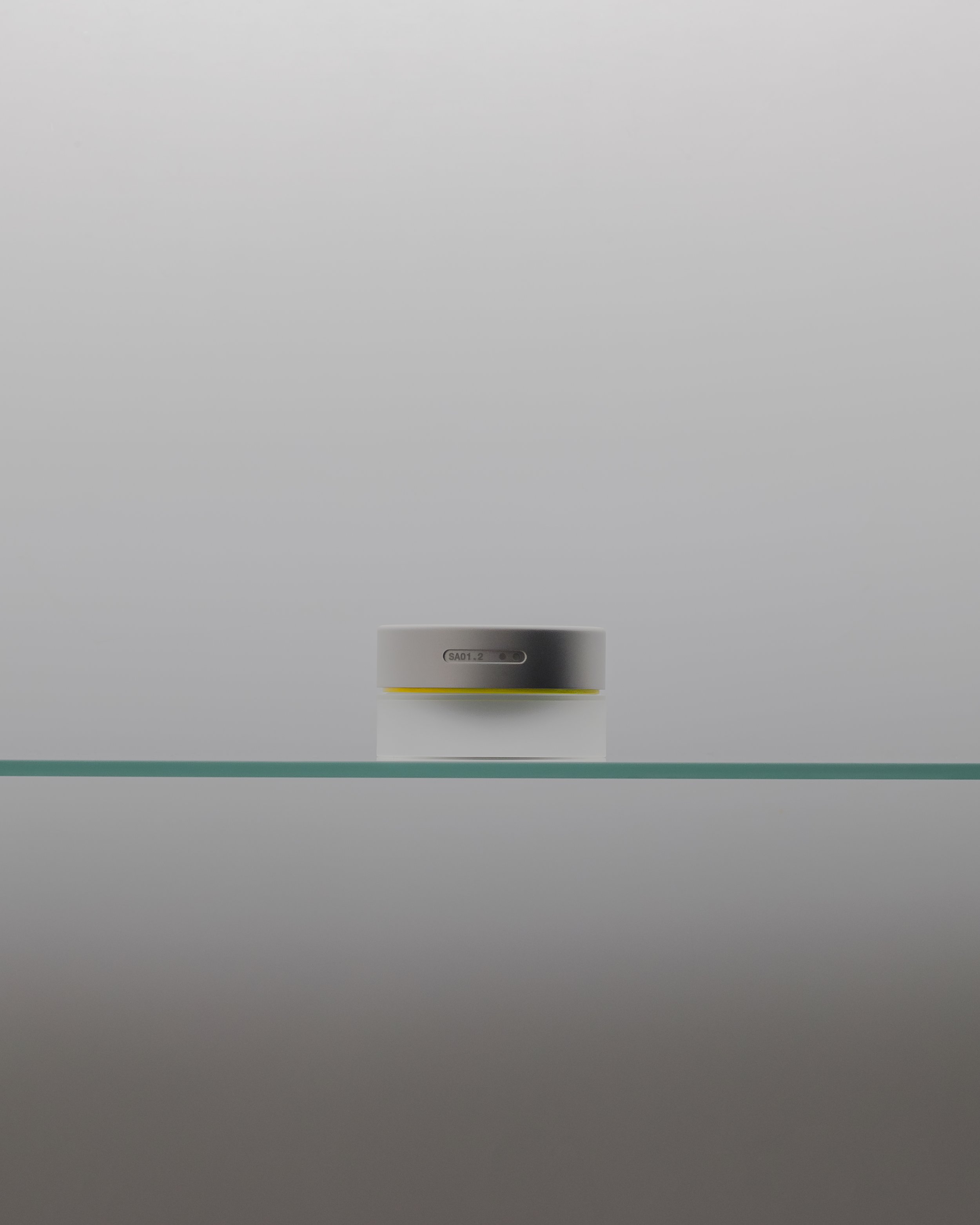

SKIN ANALYSER

The skin analyser assesses skin health like hydration and pigmentation, can diagnose dermatological conditions, detect allergens and help with detecting skin cancer early. The domed end is set on the skin, and the tool has three scanning levels: on the skin surface, sensors monitor real-time aspects like moisture, oil, temperature and pH; in the initial skin layers, light waves give insights on blood circulation and colouration; and going deeper still, it investigates cell structures for anomalies.

SPIROMETER

A traditional spirometer measures the volume of air that our lungs inspire and expire. This spirometer does a lot more. It can perform microbiome analysis, and nutrition and dietary assessments. The metabolic information it comes up with can help cancer screening. The mouthpiece is placed on the user’s lips as they exhale, and the device analyses the air and tiny saliva droplets.

OPHTHALMOSCOPE

An ophthalmoscope shows the inside of the eye. Smart Aid Kit’s version can detect neurological disorders, assess cardiovascular health and recognise auto-immune diseases. It can also help detect diabetes early on, and identify genetic disorders. The user places the flat side against their eye and looks into the camera. The tool analyses the eye’s surface and back of the eye.

To optimise usability, the user interface is designed specifically for non-professionals. The kit employs intuitive, easy-to-understand communication structured in the style of a General Practitioner consultation. Display text appears and fades through the surface of the case material to keep the user focused on the most recent instructions.. Additionally, the device delivers information verbally with text-to-speech, making it even more universally accessible.

Embedding the LLM directly into the core of the case has a number of benefits. The LLM can be specifically trained for tasks relating to the four devices. This incorporated approach speeds up analysis and decision-making without requiring constant internet connectivity, thus eliminating Cloud storage costs and patient privacy concerns.

In places where the alternative is no healthcare at all, devices like Smart Aid Kit could be a vital lifeline. They could eliminate the need to travel to doctors or hospitals in some cases, reducing both costs and time. This means early diagnosis of health conditions could be more accessible, giving underserved people—from the mother and daughter in Sierra Leone to the family in Liberia and the retiree in the Appalachian Mountains—a chance to catch their ailments early and live healthier lives.